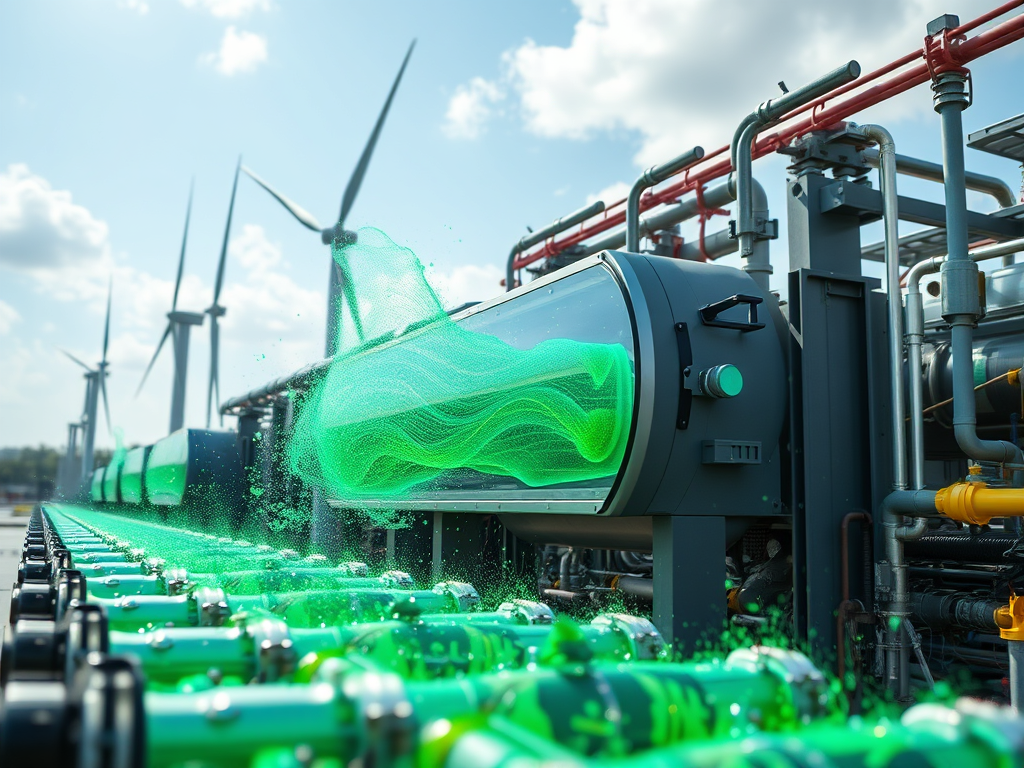

India’s renewable energy ministry has quietly adjusted expectations for one of the country’s most high-profile clean energy bets: green hydrogen.

Speaking on 11 November 2025 on the sidelines of the International Conference on Green Hydrogen (ICGH 2025) in New Delhi, MNRE Secretary Santosh Kumar Sarangi said India now expects to be producing roughly 3 million metric tonnes per annum (MMTPA) of green hydrogen by 2030 — not the 5 MMTPA originally promised under the National Green Hydrogen Mission. The 5 MMTPA mark is now more realistically expected around 2032.

This is the clearest official signal so far that India is preparing for a slower ramp than initially projected. The original 2030 target was politically important: it was positioned as proof that India could become both a global supplier and a domestic consumer of low-carbon hydrogen. That framing is now evolving.

Why the 2030 target is slipping

Mr. Sarangi linked the slippage to two external factors:

- Uncertain export markets – A large chunk of India’s early project pipeline was designed around exports to Europe and other developed markets. But European policy timelines on hard mandates and imports of green hydrogen and its derivatives (such as green ammonia) are still not fully locked in, which has dented investor confidence in large export-oriented plants.

- Shipping decarbonisation delays – Global timelines for deep decarbonisation of maritime shipping, one of the earliest expected “anchor” uses of green fuels, have slipped. If the sector isn’t forced to buy low-carbon fuel quickly, Indian projects built to supply green bunker fuels don’t get bankable demand in the near term.

In plain terms: India was counting on export pull + global regulation to justify very large electrolyser and ammonia projects. That demand signal hasn’t matured fast enough.

This tracks with a known global pattern — announced hydrogen capacity keeps racing ahead of actual, finance-closed capacity. Only a tiny fraction of the global project pipeline reaches commercial operation on schedule because projects struggle with offtake certainty, transport infrastructure, and subsidy design. Policymakers everywhere are learning that announcing “millions of tonnes by 2030” is easier than actually de-risking those tonnes.

Policy pivot: build a home market first

The message from MNRE now is not “less ambition,” but “different sequencing.”

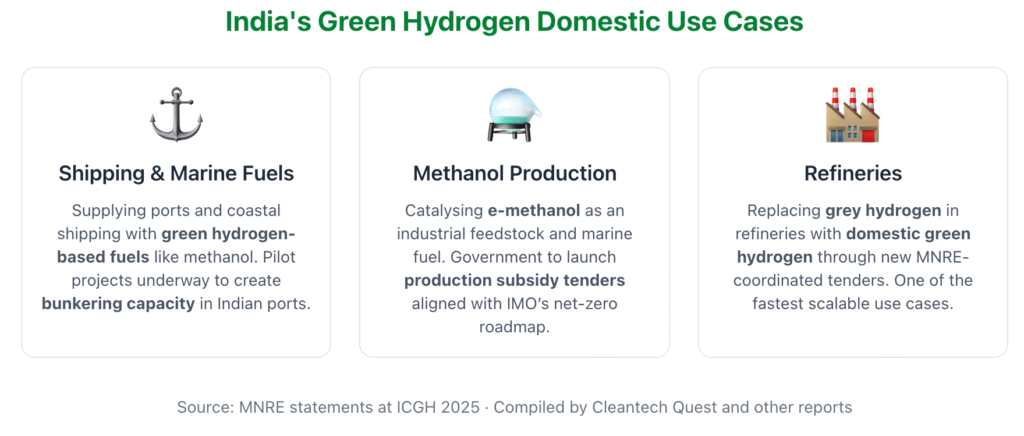

Sarangi said the centre is putting more effort into domestic demand creation and less into assuming exports will solve everything in the early years. The immediate focus areas he listed were:

This is a notable shift. Earlier messaging from the National Green Hydrogen Mission leaned heavily on India as an export hub — low-cost renewables at home producing green hydrogen, green ammonia, and green methanol for other countries. Now MNRE is openly prioritising self-consumption in hard-to-abate domestic sectors like refining, chemicals, shipping fuel, and eventually steel.

Is 3 MMTPA by 2030 still meaningful?

Yes — if it’s backed by buyers.

Independent estimates suggest India can unlock roughly 2 MMTPA of green hydrogen demand in refineries alone by 2030 by substituting a portion of today’s fossil-derived hydrogen, plus ~0.9 MMTPA in fertilisers by blending into ammonia/urea production, plus smaller but strategic volumes in city gas, chemicals, and early green-steel procurement. That domestic pull is already in the 3 MMTPA ballpark.

In other words, 3 MMTPA is not “failure.” It’s roughly the scale of what India’s own industries could realistically absorb this decade if tenders, mandates, and incentives are structured to make green molecules price-competitive with fossil alternatives.

The catch: this requires policy follow-through. Refineries and fertiliser plants operate on razor-thin cost margins. Without predictable offtake contracts, transport infrastructure, and some blend of incentives/carbon costs, they will not voluntarily lock into multi-year green hydrogen supply at a premium.

The ministry appears to know this. Sarangi noted that MNRE is now mapping transmission availability and grid connectivity before launching new tenders, to avoid announcing capacity that can’t actually evacuate power or deliver hydrogen to end-use. He also flagged an existing stress point — more than 40 GW of renewable energy projects in India that currently don’t have confirmed buyers — and said this “no orphan projects” approach will carry forward into hydrogen-linked bids.

What this means for industry (and why it matters)

1. Timelines are getting more honest.

By publicly pushing the 5 MMTPA mark to ~2032, MNRE is signalling to investors, electrolyser makers, and state governments that project build-out will be phased and demand-led. That can actually improve credibility: fewer headline numbers, more bankable offtake.

2. Domestic value chains come first.

The government has repeatedly said the National Green Hydrogen Mission is not just a climate play; it’s an industrial policy for energy security, import substitution, and jobs. The official mission documents frame green hydrogen as a way to cut fossil imports, localise clean fuels, and capture new manufacturing opportunities in electrolysers and downstream derivatives like green methanol and green ammonia.

Today’s remarks sharpen that: India wants its refineries, ports, and chemical plants to be the early anchor customers. That keeps economic value onshore and reduces exposure to volatile export demand.

3. Shipping stays strategic.

Even though global maritime timelines slipped, India is not walking away from green fuels in shipping. It’s doing the opposite: laying domestic pilots in ports like Tuticorin and building early methanol bunkering infrastructure for coastal corridors. That creates industrial learning-by-doing — experience with production, handling, safety, and bunkering of hydrogen-derived fuels — without waiting for international carriers to show up with mandates in hand.

The bigger picture

ICGH 2025 has been pitched by MNRE as a coordination forum: government, PSUs, global hydrogen alliances, refiners, ports, and technology firms all in one room to align on “what’s real, what’s financeable, and where demand will come from first.” MNRE’s own framing is that India’s green hydrogen story must now move from hype to execution — technology choices, cost curves, infrastructure, and concrete demand creation mechanisms.

The recalibration of targets — 3 MMTPA by 2030, 5 MMTPA by ~2032 — should be read in that light. This isn’t India stepping back from green hydrogen. It’s India admitting that the shortest path to scale is not exporting fuel to Europe, but decarbonising its own refineries, shipping, fertiliser, and heavy industry first, and letting export volumes emerge from that base instead of the other way around.